(![]() 2

is read "del squared" and is named the "Laplacian")

2

is read "del squared" and is named the "Laplacian")

A particular Schrödinger Equation is written to describe a set of N particles (electrons and nuclei). What does it mean? What does it mean to solve it? What are you given? What's to find?

Ψ (upper-case Greek psi, pronounced "psee" or "psigh" or even just "sigh") is a "wave" function. Given certain numbers, it assigns another number. It is a function of the three cartesian coordinates of each of the particles in the set of particles it applies to.* Thus, if you specify a structure (that is, a particular arrangement of the particles) by giving values for the 3N coordinates of the N particles in the system, Ψ will assign a particular number to that structure. The number may be positive, negative, zero, and in special cases even imaginary or complex. Let's postpone worrying about what Ψ "means" and exactly what the formula is by which it associates numbers with different structures.

*) It is also a function of time and sometimes of the "spin" of particles, but for most purposes these variables need not concern us for the time being.

We should think of Ψ

as a mathematical tool, not a "thing". What Ψ

by itself means was not truly

understood by Schrödinger, and one can argue that it is still

not understood in any straightforward physical way (although its square

has a very definite meaning, as we'll see below). Once you've gotten

acquainted with it and used it for a while, you'll be comfortable with

it. In the meanwhile you can

sympathize with physicists. On a summer afternoon boating

excursion in 1926, a few

months after Schrödinder had announced his equation at the

University of Zurich, some of the younger Zurich physicists composed

the following doggerel: Gar Manches rechnet Erwin

schon Quoted by Nobel Laureate Felix Bloch, Erwin with his Psi can do Translated by F. Bloch and J. D. Dunitz

Mit seiner Wellenfunktion.

Nur wissen möcht man gerne wohl,

Was man sich dabei vorstell'n soll.

a member of the composing party

(Physics Today, Dec. 1976)

calculations quite a few.

We only wish that we could glean

An inkling of what Psi could mean.

H is called the "Hamiltonian operator" after an analogous formulation in classical mechanics due to W. R. Hamilton, a mathematical prodigy in early 19th century Dublin. The classical Hamiltonian expresses the total energy of a system in terms of the position and momentum of its components. The Hamiltonian operator in quantum mechanics, like its classical analogue, operates on Ψ to give the potential and kinetic energies of a set of particles in any particular arrangement. It is a recipe with two parts:

The POTENTIAL-ENERGY portion of HΨ/Ψ is simple. In the typical case that the potential energy is due to the mutual electrostatic interaction among nuclei and electrons, it is the sum of contributions from all pairs of particles as calculated by Coulomb's Law (product of charges divided by distance). Thus for two electrons and one nucleus (helium atom) there would be three terms, e2 / r12, -Ze2 / r1N, and -Ze2 / r2N; where -e is the electron's charge, Ze is the nuclear charge (2e for helium), rij is the distance between i and j (1 and 2 denote electrons and N, the nucleus).

|

in units of the charge of an electron and distance, r, in Å (0.1 nm), the energy in kcal/mole is given by 332.17 x q1 x q2 / r12. |

Other forms of potential energy can also be treated (e.g. Hooke's Law for a spring, the Morse Potential to simulate breakable bonds, extrnally applied electric or magnetic fields, etc.).

Note that the potential energy (V) for a given set of positions of the particles does not depend on Ψ, although both V and Ψ are functions of the same geometric variables (the positions of the particles).

As a simple function of the distances between all pairs within the set of particles, the potential energy could be reckoned by someone with no knowledge of chemistry or physics who has a spreadsheet program (or lots of time) and has been told their charges and coordinates. The recipe HΨ then specifies that the potential energy be multiplied by Ψ, but only to be divided by Ψ in the next step when reckoning HΨ/Ψ. The potential energy thus is not dependent on Ψ (though we'll see that Ψ does depend on the shape of the potential energy function).

|

a spreadsheet to calculate the potential energy of an He atom for given x,y,z coordinates of the nucleus and the electrons...or maybe not. |

The KINETIC-ENERGY part of HΨ/Ψ looks crazy.

It is a gross understatement to say that how the HΨ/Ψ recipe calculates kinetic energy is farfetched (this was the hypothesis, based on analogy to the theory of light and deBroglie's recent theory of particle waves, which Schrödinger was testing at Debye's suggestion). Kinetic energy is intimately connected to Ψ, since it depends on the curvatures (second derivatives) of Ψ with respect to each of the 3N coordinates, evaluated at the structure in question. The mathematical expression for kinetic energy is

(![]() 2

is read "del squared" and is named the "Laplacian")

2

is read "del squared" and is named the "Laplacian")

where the sum is of

contributions from each of

the N particles;

mi

is the mass of the i-th particle;

h

is Planck's

constant;

and ![]() means

the sum of the second derivatives of Ψ

with respect to each of the x, y, and z coordinates of particle

i.

means

the sum of the second derivatives of Ψ

with respect to each of the x, y, and z coordinates of particle

i.

If you're not that far into calculus, don't worry. This just means that you make 3N separate plots of the value of Ψ as a function of each of the 3N variables (with the remaining 3N-1 positional coordinates fixed to describe the particular arrangement in question). You then see how strongly curved the plot is at the position where that one coordinate has the value for this structure. For example, consider a particular set of x,y,z coordinates for an atomic nucleus and for all its electrons but one. Hold the x and y coordinates of the final electron fixed, and see how strongly curved a plot of Ψ is as you vary only z for that electron. The sum of the curvatures for three plots varying each three coordinates of that particle i is. Because the hypothesis is that curvature is analogous to momentum squared (m2v2), you divide by the particle's mass to get something that has the dimensions of kinetic energy (mv2).

The kinetic energy for all the N particles is then summed to give a total, which needs to be scaled through division by the number Ψ and multiplication by a negative constant. Note that while the potential energy depends only on the structure for which the calculation is being performed (through Coulomb's Law), this weird calculation of kinetic energy depends on the shape of Ψ in the vicinity of the structure in question. This kinetic energy calculation is for a particular set of cartesian coordinates of all the particles. Usually it is different for other structures.

We specify "shape", rather than curvatures, because if Ψ were rescaled through multiplication

by a constant, the curvatures would increase by the same scale factor,

so that HΨ / Ψ would not change.

E does not vary with structure and will turn out to be the total energy of the system. That is, the Schrödinger Equation says,

which does not vary for an isolated set of particles.

This seems fine, except for the strange formulation of kinetic energy, which you will learn to live with because it works.

If we knew, or could guess, a formula for Ψ, then for any structure we could calculate the value of the kinetic energy through the curvatures of Ψ and its amplitude (that is, the shape of Ψ). Usually both the curvatures and the potential energy change with structure, so we might expect HΨ/Ψ to vary erratically for different arrangements of the set of particles. Still, it's not hard to imagine that there could be certain "magic" shapes of Ψ with the peculiar property that changes in the shape of Ψ (curvatures and amplitude) as we go from one arrangement of the particles to another would exactly offset changes in the potential energy. For these special Ψs, HΨ/Ψ could have a constant value (E) that is independent of the particular arrangement of the particles. This is exactly the behavior one would require for an isolated dynamic system that is not exchanging energy with its environment.

Consider two examples. Suppose Ψ were a cosine. The second derivative of a cosine is -cosine, which divided by the cosine is constant (-1), so this Ψ would work fine for the especially simple case of a constant kinetic energy that is positive (remember that the Schrödinger Equation includes multiplication by a negative constant!). This is a solution in search of a problem. The problem is "What kind of Ψ would be associated with a single particle in one dimension with a constant potential energy."

Sine would work just as well.

An even more interesting case is a negative exponential (e-ax). Here the second derivative is a2e-ax, and the kinetic energy is a constant negative value proportional to a2, so the question must have been "What kind of Ψ would be associated with single particle in one dimension with a constant potential energy greater than its total energy." Pretty weird question! (though, as we'll soon see, it applies to every electron in every atom)

Any one of these peculiar Ψs is said to be a "solution" of the (time-independent) Schrödinger Equation, HΨ/Ψ = E , since the equation will hold with a constant E for any structure at which the calculation is made. Naturally we expect that other solution Ψs would usually give different values of the constant E. Though there may be many Ψs and many Es, not any old Ψ, or in most real cases any old E, will work. E is usually quantized.

Of course different sets of particles will have completely different Hamiltonian operators, since there will be different numbers, masses, and charges of particles for calculating kinetic and potential energies. These different sets of particles will have different sets of Ψs and Es.

To build an intuition about how solutions arise it is fun to play with one dimensional problems, either in your head, or with a computer running "Erwin Meets Goldilocks", or both. The program uses Schrödinger's Equation for one dimension in the form d2Ψ/dx2 = mΨ(V(x)-E) to calculate the curvature of Ψ when given the value of Ψ and the difference between total (E) and potential (V(x)) energies. The usual difficulty, as "Erwin" shows you, is to choose E so that Ψ doesn't go shooting off to infinity, which by hypothesis is unacceptable behavior for a satisfactory wave function.

Imagining the existence of solutions and being able to write them down are quite different things. Suppose we have become so fascinated with a certain set of particles that we have sold our souls to the Devil in exchange for the set of Ψs which solve its Schrödinger Equation. Were these solutions to this mathematical puzzle a bargain, or not? What good are the Ψs?

It will of course be easy with a spreadsheet to work out what E goes with each Ψ. All that must be done is to pick an arrangement (any arrangement) of the particles and calculate HΨ/Ψ. Note in passing that if we didn't trust the Devil, we could ask a patient friend to calculate E for many different structures. If Ψ is the real thing, E will always come out the same. Still, what good are the Es?

One hypothesis of quantum mechanics is that these values of E are the only values of total energy that the set of particles can possess (unless it is in the process of changing from one "stationary state" to another). Remarkably enough this hypothesis seems to be consistent with experimental reality. The model works! This is why we hold our noses and swallow hard to choke down Schrödinger's implausible formulation of the kinetic energy.

A second hypothesis is that the Ψ associated with a certain E has a fantastic interpretation. Like Ψ itself, the value of Ψ2 varies with changing structure. For any arrangement of a set of particles, the magnitude of Ψ2 is proportional to the probability that the set of particles with energy E will find itself in this arrangement. That is, if we study a system with energy E long enough, it will spend in each arrangement a fraction of time proportional to Ψ2 evaluated for that arrangement. Similarly, if at a given time we sample a very large number of identical systems with the same energy, the fraction with a particular arrangement will be this value. The latter case is most often encountered in chemical experiments involving many molecules.

|

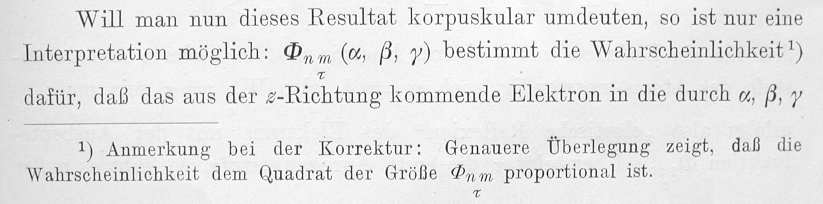

That probability should be proportional to Ψ2 is certainly not obvious, even though there is an analogy in classical mechanics. The following passage shows that Max Born, the physicist who invented this idea, half a year after Schrödinger invented quantum mechanics, initially thought Ψ itself should be interpreted as probability. He altered the interpretation to Ψ2 in a footnote added just before his first paper on the subject went to press. |

Z. Physik, 37, 863-876 (1926) "If one wishes to view this result in terms of particles, only one interpretation is possible: Φnm(α,β,γ) denotes the probability 1) that the electron entering in direction z should exit in the direction α,β,γ... [Don't be worry that Born refers to direction rather than position and uses Φ rather than Ψ. The problem he was treating involved collision between an electron and an atom, but the question of probabilistic interpretation of the wave function is fundamentally the same one we are dealing with.] |

and why Ψ2 is

actually "probability density".

Quantum mechanics also supposes that the only legitimate questions to ask about nature are ones that deal with these probabilities and averages. This hypothesis is expressed in the Uncertainty Principle. The solution of the Schrödinger Equation, Ψ, tells us everything we can possibly know about our system of particles, including how the system will change in time if it interacts with light or some other "perturbation". You'll have to wait for subsequent courses to begin using time-dependent quantum mechanics to learn how Ψ changes in time. We are looking at "stationary states" where Ψ itself is not changing with time even as the particles are whizzing around to give the probability distribution described by Ψ.

So the Devil would be giving us pretty good value for our souls, but it would be appealing to cut out this middle man and solve the Schrödinger Equation for a molecule by ourselves. Unfortunately, the equation involves functions (Ψ) of many (3N) variables, and this is generally hopeless when second derivatives are involved. Usually there is no function that can be written in a finite number of terms that would be a solution. There are two things we can do:

(1) Cut down on the number of variables(2) Settle for wrong Ψs which are close to the true ones.

A good place to start in cutting down on the number of variables is to hold the nuclei fixed. Because they're so heavy compared to the electrons, they are lethargic and don't contribute nearly as much kinetic energy. For purposes of understanding how the electrons behave we will ignore curvature of the wavefunction with respect to nuclear position, which corresponds to nuclear kinetic energy, but we will still use the nuclear charges and positions in calculating the potential energies. After making this "Born-Oppenheimer" approximation, we have a much simpler problem of ψe, the electronic wave function (we've changed to lower case psi for this partial wave function). This is a function of only 3Ne variables, where Ne is the number of electrons. As the nuclei move from one arrangement to another, the electronic wave function will change shape, but the variables that appear in the electronic wave function itself are the positions of the electrons only. Still the Schrödinger equation is too tough to solve, not only for a molecule, but even for a typical atom.

Is there anything we can hope to solve?

We can't do the helium atom (one nucleus, two electrons), but we can do "hydrogen-like" atoms (one nucleus, one electron; He+, C+5, U+91, etc.).

|

This involves a mathematical trick. Since the potential energy of such an atom depends only on the distance between the nucleus and the electron, we can be clever and work in spherical polar coordinates (right), so that the potential energy will depend on only one of the three space variables. In this special case it is possible to write the one-electron wave function as a product of three simple functions, each involving only one of the spatial variables: Such a function has a formal name, nlm, given by its quantum numbers, and an informal name. For example: R, the first function in the product, depends only on the distance, r ; each of the others depends only on one angle. Each angular function has an upper-case Greek name ("theta" or "phi") corresponding to its lower-case argument. The component functions (up through 3d orbitals) are given in the columns of the following Table. |

|

Table for Hydrogen-Like Wave Functions

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1) Why should I bother? The table allows you to write down the TRUE wave function for any one-electron atom (up through 3d orbitals; books like Pauling and Wilson give tables that go up through 6h! ). Once you can write them you will be as powerful as anyone else in the world in the way of writing real, exact, time-independent electronic wave functions. By squaring them you can find out for yourself what the various states of one-electron atoms look like without depending on some "expert" (who might not really understand anyway).

2) Where did these formulae come from? This is not our business. They were discovered 50 to 150 years before quantum mechanics by people with names like Legendre and Laguerre who were learning to solve differential equations with applications in acoustics. When quantum mechanics came along the solutions to its equations were there waiting. This is a very standard set of functions for three dimensions with an increasing number of nodes.

3) How will I ever be able to remember such complicated formulae? You don't have to, though it is useful to think carefully about the variable parts (see problems below). Most of the complexity comes from constants that are included for two reasons. First, to "normalize" the functions, i.e. to scale them so that the integral of the squared orbital (probability density) over all space is unity. Second, to allow using the same formulae no matter what the nuclear charge (Z) or, in some cases, the value of n. Often, as when calculating kinetic energy, we're interested in shape, not size, and we can ignore the constant multipliers.

The point of giving you this table is not to make you suffer with algebra, and certainly not to make you memorize all the formulae. The idea is to help you have the fun of constructing a few real wave functions and using them to ask such questions as "Where is the highest density in the electron cloud of a 2p or a 2s orbital?" and "What does an orbital really look like. Have books and teachers been telling me the truth or not?"

Exact electronic wave functions can be written down only for this kind of one-electron atom. As soon as a second electron is included, you have to worry about two more potential energy contributions, the variables no longer separate neatly, and there are no exact mathematical solutions. Still, exact solutions for one-electron atoms, and approximate solutions for other atomic and molecular systems, agree so well with experiment that no informed person whom I know, or have heard of, doubts the validity of the quantum mechanical hypotheses.

One of the most exciting areas of organic chemistry over the past half-century has been determining what approximations are valid for applying quantum mechanics to real organic molecules. This has happened in two areas):

(1) Developing reasonably accurate numerical calculations, (this has depended heavily on advances in computer technology)(2) Developing an intuitive, quantum-based model to undergird and supplement the classical molecular model for qualitative understanding of organic chemistry.

We'll use programs a little, but mostly we'll focus on the second, intuitive approach.

1) Try writing out a few hydrogen-like atomic wave functions. You just need to select a nuclear charge (Z) for the one-electron atom and a set of "quantum number" subscripts to name the wave function. The m name sometimes has both a number, used in choosing Θlm(θ), and an appended trig function, used in choosing Φm(φ). For example:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thus, the 2px orbital uses R21(ρ), Θ11(θ), and Φ1cos(φ) to give |

|

|

or collecting all the constants as K, |

|

2) Where is the maximum e-density in a 1s wave function, how large is it, how does it vary with nuclear charge and principal quantum number? How far out does the electron density extend? [Note that for locating the maximum, you don't need to consider the complicated constants. If you're ambitious, find the location of maximum density for the 2s wave function.]3) The functions look complicated because of the intricate constant multipliers, which just scale the functions so that they are normalized; that is, so that the integral of the squared wave function over all space is 1 (as the sum of all probabilities must be). If you're only interested in shape, energy, and relative, rather than absolute, probabilities, you can drop them off. So rewrite the table dropping off the multiplicative constants (not the ones in exponents) to see more clearly what gives orbitals their distinctive shapes. Try sketching 2s and 2p wave functions. Think about what you're showing, it's not trivial. Since it is hard to plot in 4 dimensions, you will have to decide how to simplify your plots. See if you can figure out where the 2px, 2py, and 2pz orbitals get their x, y, and z names. (Hint: try making a partial change from polar variables to x, y, z using the definitions in the figure. Note, for example, that r cos(θ) = z)

(Hint: Express the total density by summing the densities for each of the three wave functions - remember to square the individual wave functions to get densities before summing.)

Compare with the figures to the right and below from a recent organic text.

5) Below are five plots of 2p orbitals. Figure out how the plots were done (i.e. How many dimensions are being shown? What are the axes? How is the magnitude being plotted?) [Note that in the first graph the solid line is a squared function, while the dashed line multiplies the solid line by x-squared, you may neglect the dashed curve, which will be discussed in class.]

6) For a real treat you can create and manipulate your own H-like wave functions (or "orbitals"), generating pictures like the lower left frame above, by using Dean Dauger's program (for Mac, i-Pod touch, i-Phone) "Atom in a Box" which you can download from his site).

If you are at Yale, you may register the copy for use on a Mac at Yale under our site licence. AiB is a super program. It allows you to view and rotate the atomic orbitals, and to make slices through them. The main window plots the square of the wave function (probability density) of the electron as it would appear to the eye, if the eye could see such a thing. That is, the intensity of the light is proportional to the total probability density summed (integrated) along the line of sight. The window on the right, activated by clicking "slice" on the bottom of the display, shows a two-dimensional slice through the picture on the left with intensity proportional to the magnitude of psi-squared at the corresponding position on the slice plane. The height of the slice plane on an axis running in and out of the screen is adjustable by the slider bar between the two windows.

The color of the display can be adjusted (menu at the top of the window, or under display/view) to show electron density alone (Standard 3-D), or to add colors to show the sign of the wave function ("Phase as Color"; for chemical purposes you will want to turn off "Show Time Evolution" under Display), or to give a stereoview with red/cyan glasses (3D).

The only problem for our purposes is that AiB was designed for physics, so it starts with the physicist's functions with orbital angular momentum, rather than the chemical combinations, which are "space fixed". [Neither of these is wrong. It's just that one is a more convenient starting point for typical physics problems, where the atoms are isolated, and the other for chemical problems, where there are other atoms in the neighborhood.) The difference is apparent when you examine 2p orbitals:

n = 2, l = 1, m = 0 looks just fine and is the 2pz orbital of chemistrybut n = 2, l = 1, m = 1 looks really weird

(especially if you click "Show Time Evolution" in the "Display" menu. Best to keep Time Evolution off for our purposes to avoid sensory overload. As beginning chemists we don't need to worry about complex numbers and time evolution)To make the (2,1,1) 2p orbital "chemical" (i.e. space-fixed) click "Superposition" in the window and set the second function to be n = 2, l = 1, m = -1. Down at the bottom of the right window make sure probability is 0.5 and phase is 0 (click on them to adjust). What you are doing is adding together equal parts of two physics orbitals. Then set the phase of the second orbital in the combination to pi to generate a different chemical orbital. What are the orbitals you have generated?

You can make other mixed, or "hybrid" orbitals, such as between n = 2, l = 0, m = 0 (2s) and n = 2, l = 1, m = 0 (2pz). Watch how the shape changes as you drag the red "thermometers" to change the ratio of s and p orbital and go from one pure orbital to the other.

As you twiddle the thermometers keep track of the "probability" of each component in the "Information" table at the bottom (click on the thermometers to adjust which component you're monitoring). Can you guess what an sp3 orbital is? We'll see soon.If you create a particularly good hybrid, you might want to save it with the "Save Orbital" option in the "File" menu (clover-S). You can load some useful hybrids from the "Example Orbitals" folder that loads with the AiB program.

|

|

|

|